メローニはムッソリーニを尊敬している?――その前提自体が、イタリア政治をまったく理解していない

日本語圏ではしばしば、イタリアの首相ジョルジャ・メローニが 「ムッソリーニを尊敬している極右政治家」であり、 日本で言えば高市早苗氏と同種の存在だ、という語られ方がなされる。

だが、この理解は二重の意味で危険だ。

第一に、それは事実として正確ではない。 メローニは、国会議員として、党首として、首相として、 ムッソリーニを肯定・称揚する発言をしていない。 彼女が問題視される際に持ち出されるのは、未成年期の発言であり、 公職に就いてからの行動ではない。

第二に、より深刻なのは、 この誤った前提のもとで、 メローニと高市氏が「同じ右派」「同じ危険性」として 雑に同列化されている点だ。

未成年・公職前の発言と、 成人後・現職国会議員としての行動を、 同じ重さで扱うことは、厳しさではなく思考停止である。 責任の段階を消し去った比較は、 政治を警戒しているように見えて、 実際には危険を見分ける力を弱める。

さらに言えば、イタリアと日本では、 「戦前」と「独裁」に対する社会的記憶の重さが決定的に異なる。 イタリアではムッソリーニは再評価不能な過去であり、 政治家はそこから距離を取ることを制度的・社会的に強制される。 一方、日本では戦前体制との断絶が曖昧なまま残り、 戦前右派的な国家観が、現在の政治に滑り込みやすい。

この違いを無視して、 メローニと高市氏を同等に扱うことは、 比較ではなく混同であり、 分析ではなくラベル貼りにすぎない。

本稿では、 イタリアにおけるムッソリーニの位置づけを確認したうえで、 なぜ「メローニ=ムッソリーニ」「メローニ=高市」という図式が成立しないのか、 そして日本の右派がこの同列化に安易に乗ることが、 なぜ政治的に危ういのかを整理していく。

イタリアでムッソリーニは「再評価の対象」ではない

ムッソリーニは、イタリアでは「功罪が分かれる歴史的人物」ではない。

- 国家を強くした指導者

- 秩序を回復した政治家

- 評価が割れる存在

こうした語り方自体が、イタリア社会では強い警戒の対象になる。

なぜなら、ムッソリーニは「独裁者だった」だけではなく、イタリアにとって国家崩壊の具体的経験と直結しているからだ。

戦争判断の誤りは、単なる失点では終わらなかった。

イタリアは占領と内戦に引き込まれ、社会は分断され、国家の統合そのものが傷ついた。

この経験がある限り、ムッソリーニは「再評価」ではなく警告として記憶される。

もちろん、イタリアにもムッソリーニ懐古の空気がゼロではない。

だがそれは主流の歴史評価ではなく、周縁に残るノスタルジアに近い。

少なくとも公的な議論の場で、ムッソリーニ肯定を正面から掲げれば、政治的コストが発生する。

つまり、イタリアにおけるムッソリーニは「意見が割れる人物」ではない。

民主主義を壊し、国家を破局へ導いた存在として、制度と記憶の中に固定されている。

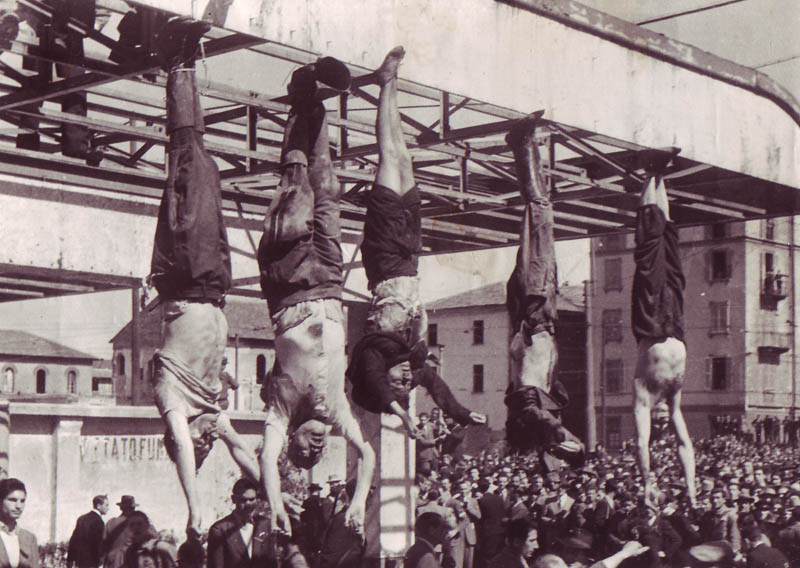

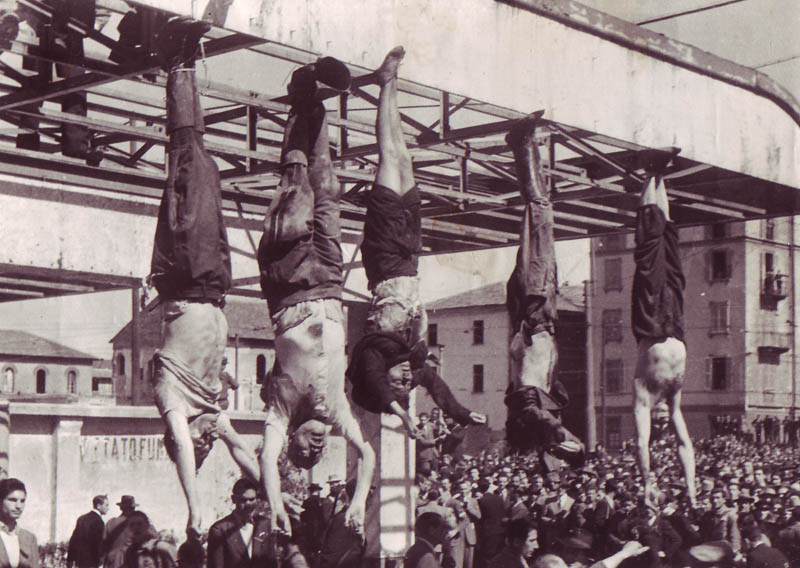

「逆さに吊るされた独裁者」が意味するもの

処刑後、逆さに吊るされ公開されたベニート・ムッソリーニと側近らの遺体。

イタリアではこの光景は「復讐の美談」や「英雄の最期」として語られることは少なく、

独裁が民主主義を破壊した末に迎えた結末を、社会が共有するための記憶として位置づけられている。

1945年、ムッソリーニは逃亡の末に捕らえられ、処刑された。

その遺体はミラノのピアッツァーレ・ロレートで逆さに吊るされ、公開された。

この出来事は「過激な報復」や「暴徒の残酷さ」としてだけ語られるべきものではない。

政治的に重要なのは、独裁者は死後も“象徴”として生き続けるという現実だ。

独裁は、倒れても神話化されれば復活する。

だからこそイタリア社会は、ムッソリーニを「英雄」として残さないために、象徴としての権威を破壊して終わらせた。

これは暴力の肯定ではなく、独裁を美談にしないための記憶の固定である。

そのためムッソリーニは、

- 懐かしむ対象にならず

- ロマン化されず

- 「強い時代」の象徴にもなりにくい

「二度と戻ってはいけない道」の象徴として位置づけられる。

そして、この記憶がある限り、現代の政治家がムッソリーニを正面から肯定することは、政治的に成立しない。

それでも「メローニ=ムッソリーニ」論が出てくる理由

それでもメローニがムッソリーニと結びつけて語られ続けるのは、偶然ではない。

その背景には、彼女の政治的出自と、外部から見たときの「分かりやすさ」がある。

メローニは、旧イタリア社会運動(MSI)を源流とする政治的系譜の中でキャリアを始めた。

この系譜が「ポスト・ファシズム」と呼ばれてきたことは事実であり、

外部からは疑念の目で見られやすい土壌がある。

ただし重要なのは、「ポスト・ファシズム」はファシズムの継承を意味しないという点だ。

それは、ファシズムを制度として否定した後に生まれた政治空間であり、

過去を肯定することも、自由に参照することもできないという制約を内包している。

この制約があるからこそ、メローニは政治的にムッソリーニを参照できない。

にもかかわらず、外部からは「系譜」だけが切り取られ、

単純化された物語として消費されやすい。

加えて、彼女が15歳前後の未成年時代に、

- 「ムッソリーニは複雑な人物だった」

- 「一部の社会政策には評価できる点があった」

といった趣旨の発言をしたことが、現在も繰り返し引用されている。

しかし、ここで起きているのは検証ではない。

現在の政治行動だけでは作れない人物像を、過去の断片で補強する作業に近い。

議員になってからの発言や政策は複雑で、評価が割れる。

一方、未成年時代の発言は切り取りやすく、ラベル化しやすい。

その結果、「15歳の発言」だけが現在の文脈から切り離されたまま生き残る。

メローニはCPACでも演説している────だが、それは「ファシズム肯定」を示すものではない

メローニは米国保守派の政治イベントCPAC(Conservative Political Action Conference)でも演説している。 この事実だけを見ると、日本では「ほら、極右ネットワークだ」「ムッソリーニ的だ」と短絡しがちだ。 だが、ここでも論点を混同してはいけない。

CPAC登壇が示すのは、第一に国際保守(とくに米国保守圏)との接続であり、 第二に「自分は体制外ではなく、体制内で統治する保守だ」という対外シグナルである。 少なくとも、CPACの場でムッソリーニを称揚したり、ファシズムを肯定したりする発言が メローニ政権の公式路線として提示されたわけではない。

むしろメローニが繰り返しているのは、「西側」「民主主義」「同盟」という枠内での自己位置づけだ。 ここで見落としてはいけないのは、国際的な保守連携と歴史的ファシズムの肯定は同義ではない、ということだ。

だからこそ、「CPACで演説した」→「ムッソリーニ肯定だ」という短絡は、 イタリア政治の制度的文脈を無視した読み違いになる。 論点は、象徴的ラベルではなく、実際にどの立場で何を正当化し、何を政策として実装しているのかで判断すべきだ。

重要なのは、こうした国際イベントへの登壇そのものではなく、 その後の政策判断や制度運用において、何が正当化され、何が実行されたのかという点である。

さらに重要なのは、日本で語られる「CPAC」と、米国のCPACが置かれている政治的文脈は、まったく同一ではないという点である。

日本におけるCPAC関連イベントは、統一教会や幸福の科学といった宗教カルト団体が関与してきた経緯があり、 政治・宗教・動員が不透明に結びついた場として問題視されてきた。

一方、米国のCPACは、是非は別としても、制度化された政党政治とロビー活動の延長線上に位置づけられるイベントであり、 宗教カルトによる組織的動員を前提とした場ではない。

この違いを無視したまま、「CPACに登壇した」という一点だけでメローニを日本の政治文脈に当てはめることは、 比較ではなく誤認であり、分析として成立しない。

メローニのMSI発言は「肯定」ではなく「制度史の説明」

メローニは、イタリア社会運動党(MSI)について、 「敗戦後の共和制イタリアにおいて、多くの人々を民主主義へと橋渡しした役割を果たした」 と述べている。

この発言だけを切り取ると、あたかもファシズムやムッソリーニを肯定しているかのように見える。 しかし、ここで語られているのは思想評価ではない。

メローニが説明しているのは、戦後イタリアの共和制が、 体制外に追いやられかねなかった右派勢力を、 議会制民主主義の枠内に組み込んだという制度史的事実である。

MSIは違憲政党ではなく、選挙に参加し、議会政治の中で活動した合法政党だった。 その意味で、共和制右派の一部として機能していた、という説明に過ぎない。

重要なのは、同じ文脈の中でメローニ自身が、 ファシズムは民主主義を停止させ、 ユダヤ人に対する忌まわしい人種法を行った体制であったと明確に断罪している点である。

説明と称揚は別物である。 この区別を無視することこそが、 「メローニ=ムッソリーニ」という誤った同列化を生む。

この点を裏づける 一次資料 として、2008年にイタリア紙『コッリエーレ・デラ・セーラ』が報じた メローニ本人の発言が残されている。

当時、党内外で「ファシズム/反ファシズム」をめぐる論争が激化する中で、 メローニはファシズム礼賛を避け、議論の道具化を戒めつつ、 自由・民主主義・平等・正義といった憲法秩序に基づく価値を基準に語っていた。

ここで重要なのは、彼女が過去の体制を政治的に称揚していない点である。 示されているのは思想の正当化ではなく、 戦後イタリアにおいて極端な政治勢力をいかに制度の枠内に組み込んできたかという 制度史的な説明にすぎない。

この一次資料は、「メローニ=ムッソリーニ」という同列化が、 後年の切り取りや印象操作によって作られたものであることを、 当時の記録そのものによって否定している。

決定的に重要なのは「いつの発言か」

政治分析において、「いつの発言か」は決定的に重要だ。

公的権限を持たない段階の発言と、国家権力を担う立場での言動とでは、

評価の基準が根本的に異なる。

問題とされているメローニの発言は、

- 未成年時代

- 公職に就く以前

- 思想形成の初期段階

- 若者向け政治組織という閉じた環境

でなされたものだ。

さらに重要なのは、15歳という年齢そのものが持つ意味である。

15歳は、社会を代表する立場にある年齢ではない。

政治的責任を負う主体でもなく、

価値観や世界観が形成途上にある未成熟な段階にある。

この年齢は、

- 社会経験が限られており

- 情報環境も大人とは大きく異なり

- 周囲の影響を強く受けながら

- 試行錯誤を通じて考えを更新していく時期

にあたる。

つまり15歳とは、評価を固定される年齢ではなく、成長し、変化することが前提とされている年齢だ。

民主主義社会において、未成年期の発言をもって、 その後の人生や政治的立場を拘束し続けるのであれば、 人は学び、考えを改め、成熟していく可能性を否定されることになる。

それは責任の追及ではなく、変化の可能性を否定する発想に近い。

だからこそ、政治家を評価する際に見るべきなのは、

「15歳のときに何を言ったか」ではない。

成長し、権限を持つ立場に至った後に、何を選び、何を語らず、何をしていないかである。

重要なのは、メローニが議員になってから、 ムッソリーニを肯定・称揚する発言を繰り返していないという事実だ。

未成年時代の発言を切り取り、 数十年後の現職首相の政治思想の証拠として扱うことは、 分析ではなく、時間を停止させたラベリングに近い。

メローニはムッソリーニを肯定しているのか?

答え:肯定していない。

ジョルジャ・メローニは、

- 国会議員として

- 党首として

- 首相として

ムッソリーニを肯定・称揚する発言をしていない。

ここでいう「肯定していない」とは、単に「好きだ」「尊敬する」と言っていないという意味ではない。

ムッソリーニを政治的参照枠(模範・正当化の根拠)として持ち出し、現代政治の正当性に接続する――その種の発言や語りをしていない、という意味である。

むしろ、公的な場では一貫して次の立場を取っている。

- ファシズムは民主主義と両立しない

- 独裁体制は否定されるべき過去である

- 人種法・言論弾圧・戦争責任は明確な過ちである

これは単なる「形式的な否定」ではなく、イタリア政治の現実に即した態度でもある。

イタリアにおいてムッソリーニは、議論の材料として自由に参照できる歴史人物ではなく、民主主義崩壊の象徴として強い社会的記憶に固定されている。

現職の政治家がこれを肯定すれば、それ自体が政治的破綻を招く。メローニがその線を越えないのは、戦術ではなく政治的条件でもある。

さらに重要なのは、彼女の政治が「ムッソリーニの復活」を旗印にして組み立てられていない点だ。

右派ポピュリズムの争点(移民・治安・家族・国境管理など)を語ることと、20世紀の独裁体制を肯定することは同義ではない。

少なくとも、議員就任以降のメローニの言動から、ムッソリーニを政治的参照枠として肯定している事実は確認できない。

言い換えれば、彼女の評価は「15歳の発言」ではなく、権限を持つ立場に至ってからの言動――何を言い、何を言わず、何を政策として選んだか――で行うべきである。

メローニの「15歳の発言」と

高市の「議員としての行動」は同列ではない

この二つを同列に扱う議論が成立しない理由は、単なる年齢差ではない。

問題の本質は、民主主義社会において「いつ」「どの立場で」「どの責任を負って」なされた言動かという点にある。

政治とは、個人の内面や思想傾向を鑑定する営みではない。

それは、権限を持つ者が、その権限と象徴性をどう扱ったかを検証する制度である。

したがって、未成年で公的権限を一切持たない段階の発言と、

国会議員として国家権力の一部を担う立場での行動を、

同じ基準で評価すること自体が、政治分析として誤っている。

メローニに関して繰り返し引用される発言は、15歳前後の未成年時代のものであり、

- 公職に就く以前

- 政策決定権も行政権限も持たない立場

- 社会経験・情報環境が限定された思想形成の初期段階

でなされた発言だ。

この段階の発言を、数十年後の首相としての統治姿勢と直結させるのは、

政治分析ではなく人物像の固定(ラベリング)に近い。

一方で、日本で問題とされた事例は、

すでに公職者として影響力と説明責任を伴う立場にあった人物の「具体的行動」である。

この差は決定的だ。

ネオナチ団体代表との写真撮影(2014年)

2014年9月、高市氏(当時総務相)が、ナチス思想を信奉する日本のネオナチ団体代表の男性と、国会内で一緒に写真撮影していたことが報道された。

問題視されたのは「一緒に写っていた」からではない。

現職の国会議員(しかも閣僚)が、国会という国家の象徴空間で、ナチズムを掲げる人物と写真に収まったという行為が、政治的意味を持つからだ。

ここで重要なのは、写真が持つ「機能」である。

写真は説明より先に流通し、文脈を剥ぎ取ったまま拡散する。さらに極端な思想を掲げる側にとっては、写真はしばしば「権威の借用」として利用される。

つまり、政治家が写真に応じた時点で、意図にかかわらず相手に政治的資源を提供してしまう可能性がある。

- 撮影時点で高市氏は現職の国会議員であった

- 相手はナチス思想を信奉する団体の代表であった

- 撮影場所は国会内(公的・象徴的空間)であった

この件に関し、高市氏側は「男性がネオナチ団体代表だとは知らなかった」とし、不可抗力であったと説明した。

しかし、この説明は政治的には不誠実だと言わざるを得ない。

仮に本当に「知らなかった」のだとすれば、問題は二重になる。

- ナチズムを掲げる団体や人物について、国会議員として最低限の認識すら持っていなかった

- その知識不足のまま、国家の中枢である国会内で無警戒に写真撮影に応じた

政治家にとって「知らなかった」は、免責ではない。

それはしばしば、危機管理の欠如と職責に必要な基礎知識の欠落を意味するからだ。

とりわけ閣僚級の立場であれば、本人の知識だけでなく、秘書・スタッフを含む体制として「誰と接触するか」を管理する責任がある。

つまり「知らなかった」という説明は、

(A)本人の知識不足、または

(B)スタッフ体制の不備(フィルタリング不全)、または

(C)その両方

を示す。いずれであっても、政治的責任は残る。

ナチズムは単なる過激思想の一つではない。

大量殺戮と民主主義の崩壊を現実のものにした、20世紀最大級の政治犯罪と結びついた思想である。

その思想を信奉する人物と国会内で写真に収まる行為は、意図の有無にかかわらず、日本の立法府の姿勢として解釈されうる。

だからこそ「知らなかった」は、責任を軽くする言葉ではなく、国会議員としての適格性(知識・警戒心・判断力)を逆に問う言葉になり得る。

ここで問われているのは「同調したか否か」ではない。

同調の余地を相手に与え、権威を貸し、文脈を再生産する行為を防げたかという点である。

ヒトラー関連書籍への推薦文寄稿(2014年)

同じく2014年、高市氏が『ヒトラー 選挙戦略』(田中吉廣著)という書籍に推薦文を寄せていたことも問題視された。

ここでも論点は「本の内容が分析だったか礼賛だったか」だけではない。

推薦文とは、単なる感想ではなく社会的な信用の付与であり、政治家が関与すればその行為は不可避的に政治的意味を帯びる。

- 内容に一定の価値判断を与える

- 著者やテーマに公的信用を付与する

- 政治家としての判断が不可避的に反映される

ヒトラーは「選挙技術の一例」ではなく、大量殺戮と民主主義崩壊を現実化した人物である。

その人物を扱う書籍に、現職議員が推薦という形で関与することは、政治的距離感の問題として問われる。

さらに重要なのは、推薦文が「読む人の読み方」を規定する点だ。

政治家の名が入ると、読者は内容以前に「公的に承認されたテーマ」と受け取りやすい。

結果として、意図せずとも危険な対象の“取り扱いを軽くする”効果が生じうる。

ここで問われたのは、内容理解の有無ではなく、立場に見合った慎重さを保てていたかである。

本質的な違いは「思想」ではなく「責任の段階」

この二つのケースの違いは明確であり、単なる年齢差の問題ではない。

- メローニ:未成年・公職就任以前の発言

- 高市氏:成人後・国会議員として公的責任を負う立場での行動

ここで比較されるべきなのは、思想の中身ではない。

政治において問われるのは、「いつ」「どの立場で」「どの責任を負って」行われた言動かという点である。

政治とは、内心や好悪を監視する場ではない。

権限を持つ者が、どのように振る舞い、その結果にどう責任を負ったかを検証する制度である。

そのため、未成年期の発言と、公職に就いてからの具体的行動を同一線上で扱うこと自体が、

民主主義における責任概念を誤解している。

責任の所在を曖昧にすれば、説明責任は形骸化する。

政治の評価は、行動ではなく印象やラベルの応酬に堕する。

それは結果として、

本当に危険な権力行使を見逃し、批判すべき対象を取り違えることにつながる。

だからこそ、この二つを「同じ問題」として並べることは、比較ではない。

責任の段階を破壊する行為であり、分析ではなく思考停止に近い。

比較が成立するためには、前提条件が揃っていなければならない。

この二つのケースは、その前提が決定的に異なっている。

イタリアにも極右は存在する──だが政治の主流にはなっていない

もちろん、イタリアにも極右的言説やネオファシズム的集団は存在する。 排外主義的な主張や、ムッソリーニを象徴的に持ち出す動きが、社会の周縁で見られるのは事実だ。

しかし重要なのは、それらがイタリア社会の中で明確に「周縁」に押し込められているという点である。 世論の感覚として共有されているのは、 「そういう人たちはいるが、主流ではない」 「距離を取らなければ政治的に危険だ」 という認識だ。

この距離感が保たれている最大の理由は、ファシズムがイタリアにとって抽象的な過去ではなく、 国家崩壊・内戦・占領・社会分断という具体的な破局の記憶として残っているからである。

さらに、イタリア共和国憲法は反ファシズムを明確な前提として成立しており、 ファシズム的組織やその再建は、制度上も政治的にも強く警戒される対象となる。 極右的言動は単なる「右の意見」ではなく、 憲法秩序への挑戦として即座に問題化される。

そのため、メディア、市民社会、学界、ユダヤ系コミュニティなどが迅速に反応し、 極右的シンボルや歴史修正主義的発言が主流政治に入り込むコストは極めて高い。

結果として、イタリアでは「極右が存在する」ことと 「極右が政治の主流になる」ことのあいだに、はっきりとした断絶が保たれている。

この前提を無視して「イタリアでも極右が台頭している」と語ることは、 イタリア社会の現実だけでなく、日本側の政治的感覚のズレを露呈させる。

この点は、現在の日本の政治状況と――決定的に異なる。

日本では、戦前体制や国家主義についての制度的・社会的な総括が曖昧なまま残されてきた。 そのため、強い国家観や排外的言説、戦前を想起させる価値観が、 「保守の一形態」「意見の違い」として、主流政治の内部に滑り込みやすい。

イタリアでは、ファシズム的言動は即座に 「憲法秩序への挑戦」として線を引かれる。 一方、日本では同様の言説が、 「議論の一つ」「思想の自由」という名目で曖昧に処理されることが少なくない。

この違いがあるからこそ、 イタリアでは極右が「存在」しても「主流」になりにくく、 日本では境界線が引かれないまま、過激な言説が政治の中心に近づいていく。

排外主義と移民制限は同じではない

この点は、現在の日本の政治状況と決定的に異なる。

しばしば混同されるが、排外主義と移民制限は同義ではない。 排外主義とは、特定の民族・宗教・出自そのものを脅威や敵とみなし、 社会から排除する思想である。 一方、移民制限は、国家が制度として入国・滞在・労働の条件を管理する 政策判断であり、民主主義国家における統治手段の一つである。

ジョルジャ・メローニの政治的立場は、明確に後者に属する。 彼女は治安、社会保障、労働市場の持続性といった 具体的な政策課題の文脈で移民管理の厳格化を主張してきたが、 特定の民族や宗教を「排除すべき存在」として名指しするような 排外主義的言説を、公的な政治路線として打ち出してはいない。

この点で、メローニの政治姿勢は、日本の右派政治家の一部、 とりわけ高市早苗氏の言動とは明確に異なる。 高市氏の場合、移民政策や安全保障の議論が、 戦前国家観や文化的優劣を想起させる言説、 あるいは歴史修正主義的な文脈と結びつく形で語られてきた。 そのため、政策論と思想的動員の境界が曖昧になりやすい。

一方、イタリアでは、ファシズムという具体的な歴史的破局を 社会全体が共有しているため、 排外主義は明確に警戒される思想として位置づけられている。 その上で、移民政策の是非は、 右派・左派を問わず制度論として切り分けて議論されている。

対照的に、日本の政治空間では、 移民制限・治安論・文化論が容易に排外主義的感情と接続され、 その線引きが曖昧なまま動員されやすい。 その結果、「移民に厳しい=排外主義」 「右派=危険」という単純化が横行し、 政策の中身や政治責任の検証が後景に退いてしまう。

メローニを高市氏と同列に「排外主義的右派」として扱う言説は、 この概念的・歴史的な差異を無視した比較である。 それは分析ではなく、 日本固有の政治的混乱をイタリア政治に投影した誤読に近い。

結論

メローニは、議員になってからムッソリーニを肯定・称揚する発言をしていない。

この点は、印象や評価ではなく、公的言動の記録として確認できる事実である。

そして重要なのは、この点においてメローニと高市氏は同列ではないということだ。

両者を「極右」「危険思想」という一語で並べる議論は、政治的責任の段階を無視している。

メローニの場合、問題とされている発言は未成年期のものであり、

公職に就く以前、権限も影響力も持たない段階での言葉だ。

その後、国会議員・党首・首相という立場に至ってから、

彼女はムッソリーニを政治的参照枠として肯定する言動を繰り返していない。

一方で、高市氏をめぐる問題は、成人後、しかも国会議員として活動していた時期の行動に関わる。

ネオナチ団体代表との写真撮影や、ヒトラーを扱う書籍への推薦文寄稿は、

いずれも公的立場と政治的影響力を伴う行為として評価されてきた。

ここで問われているのは、思想の好悪ではない。

どの立場で、どの責任を負う段階で行われた言動なのかという一点である。

この前提を無視して両者を同等に扱うことは、比較ではなく混同に近い。

さらに、イタリアにおいてムッソリーニは、誇りでも伝統でもなく、

民主主義が崩壊した具体的失敗例として社会的記憶に固定されている。

そのため、メローニはムッソリーニという過去から距離を取り続けることを、

政治的に強く求められる立場にある。

私自身が強い違和感を覚えるのは、こうした制度的・歴史的条件を無視し、

「右派だから同じ」「強硬だから同類」と短絡する日本語圏の議論だ。

それは批判として鋭いようでいて、実際には政治の危険性を正確に捉えていない。

本当に警戒すべきなのは、若年期の発言の断片ではなく、

権限を持った後に何を正当化し、何を制度化し、何を黙認していくのかという点である。

その意味で、メローニと高市氏を同等に扱うことは、分析としても、警戒の仕方としても誤っている。

結論として、メローニを評価するにせよ批判するにせよ、

高市氏と同列に置く前提そのものを疑わなければならない。

比較が成立しないものを並べても、政治の理解は深まらない。

Does Giorgia Meloni Admire Mussolini? — That Premise Itself Shows a Complete Misreading of Italian Politics

In Japanese-language discourse, you often see claims like these:

- “Meloni admires Mussolini.”

- “She’s far-right, an authoritarian-minded leader.”

- “This is a revival of Mussolini-style politics.”

- “In Japan’s context, she’s basically the same as Sanae Takaichi.”

But this framing is dangerous in two ways.

First, it is not factually accurate. Meloni has not praised or celebrated Mussolini in her capacity as a member of parliament, a party leader, or prime minister. What gets recycled instead are remarks attributed to her teenage years—statements made before she held public office or any governing authority.

Second—and more seriously—this mistaken premise becomes the basis for a lazy “same-category” comparison that treats Meloni and Sanae Takaichi as equivalent: “same right wing,” “same threat.” That comparison collapses the most important distinction in politics: the stage of responsibility.

Treating a minor’s pre-office remarks as equal in weight to actions taken by an adult politician while holding power is not “strictness.” It is intellectual shortcuts. When you erase the difference in responsibility, you weaken your ability to detect real political danger.

And there is a deeper structural gap: Italy and Japan do not carry the same public memory of “prewar” nationalism and dictatorship. In Italy, Mussolini is not a figure open to “re-evaluation”; politics is expected—socially and institutionally—to keep distance from him. In Japan, the rupture with prewar politics can remain ambiguous, which allows prewar-style state-centered thinking to slip into contemporary rhetoric more easily.

Ignoring these conditions and insisting “they’re the same” is not comparison—it is confusion. It is labeling, not analysis.

This article first clarifies what Mussolini represents in Italy today, then explains why “Meloni = Mussolini” and “Meloni = Takaichi” frames do not hold—and why the ease with which Japan’s right embraces such equivalences is itself politically risky.

In Italy, Mussolini Is Not an Object of “Re-evaluation”

Mussolini is not treated in Italy as a historical figure whose legacy is “mixed” or “debatable.”

- a leader who “made the nation strong”

- a politician who “restored order”

- a figure whose reputation is “divided”

Even this style of framing tends to trigger strong suspicion in Italian society. Why? Because Mussolini is not remembered merely as “an authoritarian leader,” but as a concrete case of national catastrophe.

The failure of wartime judgment was not a “policy mistake.” Italy was dragged into occupation and civil conflict; society fractured; the country’s cohesion itself was damaged. As long as that historical experience remains central, Mussolini is recalled not as a candidate for “rehabilitation,” but as a warning.

Yes, nostalgia exists at the margins. But it is not the mainstream historical view, and it does not carry public legitimacy. In official politics, open praise for Mussolini comes with steep political costs.

In short, Mussolini in Italy is not a figure to “argue over.” He is fixed in public memory as the person who helped destroy democracy and led the country into disaster—anchored by both institutions and collective remembrance.

What “The Dictator Hung Upside Down” Represents

In Italy, this image is rarely framed as a heroic finale; rather, it functions as a collective memory meant to prevent dictatorship from being romanticized.

The political point here is not voyeurism or “revenge.” The key is that dictators can survive death as symbols. If the symbol is mythologized, the project returns.

That is why the end of dictatorship was made unmistakably un-romantic. This is not a moral endorsement of violence; it is an argument about memory. Italy fixed the meaning of the regime as a collapse—not as a nostalgia object.

As a result, Mussolini is:

- not a figure of sentimental longing

- not easily romanticized

- not a usable emblem of “a strong era”

He is positioned as a symbol of a road society must not return to. As long as that memory holds, a sitting prime minister cannot openly praise Mussolini and remain politically viable.

Why the “Meloni = Mussolini” Narrative Still Spreads

It is not accidental that Meloni is repeatedly linked to Mussolini. There are two structural reasons: her political origins and the outside world’s appetite for “simple stories.”

Meloni began her career in a political lineage that traces back to the postwar right, including the Italian Social Movement (MSI). That lineage has often been described as “post-fascist,” which makes it easy for outsiders to view it with suspicion.

But “post-fascist” does not automatically mean “fascism continued.” It describes a political space formed after fascism was institutionally rejected—one that cannot freely praise or rehabilitate the past without crossing lines enforced by society and constitutional order.

Because of those constraints, Meloni cannot use Mussolini as a political reference point. Yet from abroad, the “lineage” alone is cut out and turned into a simplified story.

Add to that the fact that remarks from her teenage years (often summarized as “Mussolini was complex” or “some social policies were effective”) are repeatedly recycled. But what is happening here is not verification; it is narrative-building—using a fragment from the past to “prove” a present-day identity.

Policies and governing behavior after entering office are complex and contested. Teenage remarks are easy to quote and easy to label. That is why the fragment survives, detached from context.

Meloni Has Spoken at CPAC — But That Does Not Constitute an Endorsement of Fascism

Giorgia Meloni has delivered remarks at CPAC (the Conservative Political Action Conference), a major political gathering within the American conservative ecosystem. In Japan, this fact is often treated as shorthand for claims such as “she is part of a far-right network” or even “this proves admiration for Mussolini.” Such conclusions, however, rest on a fundamental confusion of political context.

Appearing at CPAC primarily signals two things. First, participation in transnational conservative networks, particularly within the United States. Second, an outward assertion that one intends to govern within existing institutional frameworks, rather than from outside them. At no point has CPAC served as a platform on which Meloni praised Mussolini or endorsed fascism as a governing model.

What Meloni has consistently emphasized instead is her alignment with the “West,” with democratic legitimacy, and with alliance-based politics. The crucial distinction here is that international conservative coordination is not equivalent to the rehabilitation of historical fascism. Conflating the two replaces analysis with symbolic labeling.

Therefore, the claim “she spoke at CPAC, therefore she endorses Mussolini” ignores the institutional context of Italian politics. The relevant question is not which stage a politician appeared on, but what positions are justified, normalized, and implemented once power is held.

This point marks a decisive difference from the current political situation in Japan.

In Japan, events branded as “CPAC” or CPAC-related have often involved organizations such as the Unification Church or Happy Science, religious cult groups that have played an active role in political mobilization. In these cases, political messaging, religious authority, and organizational mobilization have been intertwined in opaque and problematic ways.

By contrast, CPAC in the United States—regardless of ideological evaluation—operates within a conventional framework of party politics, interest groups, and institutional conservatism. It is not structured as a vehicle for cult-based political mobilization.

Ignoring this structural difference and equating CPAC appearances across national contexts turns comparison into misclassification. It obscures both the realities of Italian politics and the specific vulnerabilities present within Japan’s own political environment.

Meloni’s Statements on the MSI Are Not “Endorsement,” but an Explanation of Institutional History

Giorgia Meloni has stated that the Italian Social Movement (MSI), in postwar republican Italy, played a role in channeling large segments of the population back into democratic participation. When taken out of context, this remark is sometimes presented as evidence that she endorses fascism or Mussolini. That interpretation is inaccurate.

What Meloni is describing is not ideological approval, but a historical account of how postwar Italy dealt with political forces that could not simply be excluded from the system. The MSI was not a revolutionary movement. It participated in elections, operated within parliamentary rules, and functioned—however imperfectly—as part of the republican framework.

Crucially, in the same context, Meloni explicitly condemned fascism itself, describing it as a regime that suppressed democracy, enacted racial laws, and bore responsibility for war and repression. Explanation and endorsement are not the same.

This interpretation is supported by a primary source published in 2008 by the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera, which records Meloni’s own words at the time.

Amid intense internal debates over “fascism” and “anti-fascism,” Meloni rejected any glorification of the past regime and warned against the instrumentalization of historical labels. Instead, she framed her position around constitutional values such as freedom, democracy, equality, and justice.

What emerges from this record is not an attempt to rehabilitate fascism, but an effort to situate Italian political history within a democratic and institutional framework. The frequent equation of “Meloni equals Mussolini” is therefore not grounded in contemporary evidence, but in later acts of selective quotation and symbolic misrepresentation.

The Decisive Question Is: When Was It Said?

In political analysis, timing is decisive. The standards for speech made without public authority are fundamentally different from those for behavior and statements made by someone who wields state power.

What is cited against Meloni belongs to a period when she was:

- a minor

- not yet in public office

- in an early phase of worldview formation

- speaking within a closed youth-political environment

And the age itself matters. Fifteen is not an age that “represents society.” It is a stage of immaturity and change, where people absorb surroundings, revise beliefs, and learn through trial and error.

In a democracy, if we freeze a minor’s statement as a lifetime verdict, we deny the possibility of learning and maturation. That is not accountability; it is the denial of change.

So the proper metric is not “what was said at 15,” but what was said and done after power was acquired: what was endorsed, what was institutionalized, and what was tolerated.

And crucially: there is no evidence that Meloni, after entering parliament and rising to executive authority, has repeatedly praised Mussolini or used him as a legitimizing political reference.

Does Meloni Praise Mussolini?

Answer: No.

Giorgia Meloni, as

- a member of parliament

- a party leader

- prime minister

has not praised or celebrated Mussolini.

“Not praising” here does not merely mean she avoids saying “I admire him.” It means she does not invoke Mussolini as a political model or as a source of legitimacy for contemporary governance.

Instead, in public contexts she has maintained positions consistent with Italy’s constitutional order:

- fascism is incompatible with democracy

- dictatorship is a past to be rejected, not revived

- racial laws, censorship, and war responsibility were grave wrongs

In Italy, these are not “cosmetic” disclaimers. They reflect the political reality that Mussolini is not a usable symbol in mainstream politics. Openly praising him would carry immediate political consequences.

So whatever one thinks of her on immigration, culture, or national identity, it does not follow that her politics is “Mussolini revived.” That leap is narrative, not analysis.

If Meloni is to be judged politically, it should be on governance and policy choices after acquiring power—not on teenage fragments treated as permanent proof.

Meloni’s “Age-15 Remarks” and Takaichi’s “Actions as a Lawmaker” Are Not Comparable

These two cannot be treated as equivalent, and the reason is not simply “age.”

The decisive difference is the stage of responsibility in a democratic society: when the act occurred, from what position, and with what public authority.

Politics is not a courtroom for private thoughts, nor a moral purity test. It is the realm where public power is exercised—and where public trust must be protected.

That is why it is analytically wrong to evaluate a minor’s pre-office remarks and an elected official’s public conduct under the same standard.

What is repeatedly cited regarding Meloni concerns remarks from her teenage years—made:

- before public office

- without institutional authority

- in an early phase of worldview formation

Treating such remarks as decisive evidence of the political identity of a sitting prime minister decades later is closer to labeling than analysis.

By contrast, what drew controversy in Japan involved concrete actions taken by an adult politician while holding public office and political influence. That difference matters.

Photo with a Neo-Nazi Group Representative (2014)

In September 2014, it was reported that Sanae Takaichi (then a cabinet minister) had been photographed in the National Diet with a man identified as the representative of a Japanese neo-Nazi group. Takaichi’s side explained that she “did not know” the man’s affiliation and framed the situation as unavoidable.

But the core issue is not simply whether she was “tricked.” A photo taken inside the Diet, by a national lawmaker, can function as a form of public credibility—especially for extremist actors who seek legitimacy through proximity to power.

And the “I didn’t know” explanation is itself politically problematic. If she truly did not know, then at minimum one of the following applies:

- Insufficient political literacy for a national legislator (a failure of due diligence), or

- Institutional negligence in screening and risk management (staff failure is still political responsibility), or

- A rhetorical shield used to evade accountability after the fact.

In any case, responsibility does not vanish. “Not knowing” is not a neutral alibi for a public official; it indicates a failure of competence, oversight, or accountability.

Neo-Nazism is not “just another extreme view.” It is an ideology historically tied to mass violence and the destruction of democratic politics. Allowing such actors to obtain imagery that looks like institutional endorsement is precisely why public officials are expected to exercise heightened caution.

This is why the controversy is not about “intent.” It is about the public function of the act: providing symbolic legitimacy through an official setting and an official role.

Endorsement Blurb for a Hitler-Related Book (2014)

Also in 2014, it was criticized that Takaichi had provided an endorsement blurb for a book titled Hitler’s Election Strategy (by Yoshihiro Tanaka). Some defenders argue, “It was merely an analysis of campaign tactics.”

But the point is not whether the book claims to be “analysis.” An endorsement by a sitting politician is not an academic footnote. It functions as a public signal—a form of reputational lending that can shape how the work and its subject are received.

In politics, effects matter. Even if one insists the intention was “analytical,” the act still produces predictable consequences:

- it lends a degree of legitimacy to the theme and framing

- it supplies social credibility to the author and the project

- it invites interpretation as political messaging by an office-holder

And Hitler is not a neutral case study. He is not merely “a campaign innovator,” but the figure who enabled mass atrocities and the collapse of democratic institutions.

For a public official, attaching one’s name as an endorsement to material centered on Hitler—regardless of claimed intent—raises a question of political judgment and responsibility.

What is being questioned here is not the legitimacy of studying history, but whether an elected official, acting as an elected official, demonstrated the caution required when dealing with extremist symbolism and its public afterlife.

This is why collapsing these cases into “the same problem” is not a neutral comparison—it is a distortion.

Equating a minor’s pre-office remarks with the conduct of an adult lawmaker exercising public authority erases the very concept of political responsibility. It replaces analysis with labeling, and accountability with aesthetic judgment.

If everything is treated as equally dangerous, then nothing truly dangerous can be identified. Democracy does not fail because of teenage comments preserved in amber; it fails when power is exercised carelessly, symbols are normalized, and responsibility is evaded once authority is held.

The question, therefore, is not who once said something questionable, but who acted, from what position, and with what consequences. Any analysis that refuses to draw this line is not being “strict”—it is being intellectually lazy.

The Essential Difference Is Not “Ideology,” but the Stage of Responsibility

The difference between these two cases is clear. It is not a matter of age alone.

- Meloni: remarks made as a minor, before public office

- Takaichi: actions taken as an adult, while serving as a national lawmaker

What is being compared here is not the content of personal beliefs. The issue is at what stage of responsibility political judgment was exercised.

Politics is not a space for monitoring inner thoughts or moral purity. It is a system designed to examine how power is used, by whom, and under what institutional authority.

For that reason, equating remarks made before holding public responsibility with conduct carried out while exercising public power fundamentally misunderstands how accountability works in a democracy.

Statements made in adolescence—before entering public life—do not carry the same political weight as actions taken by an elected official entrusted with public authority. Treating them as equivalent blurs responsibility rather than clarifying it.

And once responsibility is blurred, accountability becomes easy to evade. Politics then shifts from evaluating conduct to debating impressions, from examining power to trading labels.

That is precisely why democratic systems insist on transparency and responsibility at the point where authority is exercised. Without that distinction, genuine threats become harder to identify, while superficial controversies multiply.

For this reason, placing these two cases side by side as if they were comparable is not an act of careful comparison. It is closer to a collapse of responsibility—one that ultimately weakens political analysis itself.

Any valid comparison must begin with shared conditions of responsibility. In this case, those conditions are decisively different.

Far-Right Groups Do Exist in Italy — But They Have Not Become the Political Mainstream

To be clear, far-right rhetoric and neo-fascist groups do exist in Italy. Xenophobic discourse and symbolic references to Mussolini can still be observed on the margins of society. That fact itself should not be denied.

What matters, however, is how these forces are positioned within Italian society. They are broadly understood as entities that must remain at the margins. The prevailing public sentiment is not that they represent a legitimate political alternative, but that they constitute something to be watched, contained, and kept at a distance.

The primary reason for this lies in Italy’s historical experience. Fascism is not remembered as an abstract ideology or a distant past, but as a concrete national catastrophe involving war, occupation, civil conflict, and the breakdown of social cohesion.

In addition, the Italian Republic was founded on an explicitly anti-fascist constitutional order. Fascism is treated not as one opinion among others, but as something fundamentally incompatible with democratic governance. As a result, far-right rhetoric is quickly recognized as a challenge to constitutional norms, rather than absorbed as part of ordinary political debate.

Media organizations, civil society, academic institutions, and Jewish communities respond rapidly to extremist symbolism and historical revisionism. This makes the political cost of normalizing far-right narratives extremely high.

The outcome is a clear distinction: far-right movements may exist in Italy, but they do not easily become the center of political life. The line between presence and dominance is actively maintained.

Ignoring this distinction and claiming that “Italy is also experiencing a far-right takeover” misreads not only Italian political reality, but also exposes a gap in how such dynamics are perceived from Japan.

This point marks a decisive break from the current political situation in Japan.

In Japan, the historical reckoning with the prewar state and wartime nationalism has remained institutionally and socially ambiguous. As a result, strong state-centered ideas, exclusionary rhetoric, and values reminiscent of the prewar era can more easily slip into mainstream politics, often reframed as merely “one form of conservatism” or “a difference of opinion.”

In Italy, by contrast, fascist rhetoric is quickly identified as a challenge to the constitutional order. In Japan, similar language is more often treated as part of ordinary debate, or shielded under the banner of ideological freedom.

This difference explains why, in Italy, far-right groups may exist without becoming politically dominant, while in Japan the absence of a clearly enforced boundary allows radical ideas to move closer to the center of political power.

Ignoring this contrast and claiming that “Italy, too, is experiencing a far-right surge” misreads Italian political reality and simultaneously obscures a critical vulnerability within Japan’s own political landscape.

Exclusionism and Immigration Control Are Not the Same

This point marks a decisive difference from the current political situation in Japan.

Exclusionism and immigration control are often conflated, but they are not equivalent. Exclusionism is an ideology that defines specific ethnic, religious, or cultural groups as inherent threats and seeks to exclude them from society. Immigration control, by contrast, is a policy tool through which a state regulates entry, residence, and employment conditions. It is a form of governance adopted by many democratic countries.

Giorgia Meloni’s political position clearly falls into the latter category. Her arguments for stricter immigration management are framed in terms of public security, social welfare sustainability, and labor market regulation. She has not articulated immigration policy as a project of ethnic or religious exclusion, nor has she institutionalized exclusionist rhetoric as a core political doctrine.

In this respect, Meloni’s approach differs fundamentally from that of certain right-wing politicians in Japan, most notably Sanae Takaichi. In Takaichi’s case, discussions of immigration and national security have frequently been intertwined with narratives invoking prewar state ideology, cultural hierarchy, or historical revisionism. As a result, the boundary between policy debate and ideological mobilization tends to become blurred.

In Italy, by contrast, the historical experience of Fascism functions as a clear social boundary. Exclusionism is widely recognized as a political danger, shaped by collective memory of authoritarian collapse. Within that framework, immigration policy is debated across the political spectrum as a matter of institutional design rather than ideological identity.

In Japan’s political discourse, however, immigration control, security concerns, and cultural narratives are more easily fused with exclusionist sentiment. This fusion encourages simplified binaries—“strict on immigration equals exclusionist,” or “right-wing equals dangerous”—which obscure policy substance and weaken accountability.

Treating Meloni and Takaichi as equivalent “exclusionist right-wing figures” ignores these conceptual and historical distinctions. Such comparisons do not constitute analysis; they project Japan’s domestic political ambiguities onto Italian politics and result in systematic misreading.

Conclusion

Meloni has not praised or glorified Mussolini since entering public office. This is not a matter of interpretation or goodwill; it is a matter of public record.

And this point matters precisely because, in this context, Meloni and Sanae Takaichi cannot be treated as equivalent. To label them both as “the same right wing” or “the same danger” collapses the distinction between responsibility and non-responsibility, and obscures political accountability.

In Meloni’s case, what is repeatedly cited are remarks from her teenage years—statements made before public office, before institutional authority, and before she carried responsibility as a representative of the state. After entering parliament, becoming party leader, and assuming the office of prime minister, she has not invoked Mussolini as a political reference or source of legitimacy.

By contrast, what became controversial in Japan involved actions taken by an adult politician while already serving as a member of the National Diet. Photographs with a neo-Nazi group representative and endorsement text for a book dealing with Hitler were not private thoughts, but public acts with political impact, evaluated as such.

What is at issue here is not ideological purity. It is the stage at which responsibility was exercised—and whether power was handled with the caution and judgment required of an elected official.

This is why placing these two cases side by side is not a valid comparison. It erases the distinction between pre-office remarks and actions taken under public authority, replacing analysis with superficial equivalence.

In Italy, Mussolini is not a tradition to be invoked or debated nostalgically. He is fixed in public memory as a concrete example of democratic collapse. That is precisely why Italian politics demands distance from him, and why Meloni is politically constrained to maintain that distance.

What troubles me most is how easily parts of Japan’s political discourse ignore these historical and institutional differences, and instead rely on slogans like “history repeats itself” or “the strong right returns.” Such framing feels persuasive, but it dulls our ability to identify where real democratic risk actually lies.

What should be examined is not fragments of teenage speech frozen in time, but how authority is exercised once power is obtained—what is normalized, what is excused, and what responsibility is accepted or avoided.

For that reason, evaluating Meloni does not require defending her, nor does criticizing her require distortion. But treating her as equivalent to Takaichi is neither fair comparison nor serious analysis.

Without respecting these distinctions, political criticism loses its precision. And without precision, political analysis loses its meaning.

参考文献(References)

- Italian Constitution (Official English Translation), Senate of the Italian Republic

- BBC — Italy’s PM says fascism is ‘consigned to history’. Not everyone is so sure (May.30, 2024)

- Reuters — Meloni Distances Herself from Mussolini (Apr.25, 2023)

- ANSA-MSI had important role in Italian history says Meloni (Apr.25, 2023)

- Encyclopaedia Britannica — Benito Mussolini

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum — Fascist Italy under Mussolini

- AFP-内閣改造で起用の2議員、ネオナチ団体との関係を否定

- Huffpost-女性閣僚の辞任相次ぐ安倍内閣 高市早苗氏が推薦文を寄せた「ヒトラー選挙戦略」とは?

※本記事の分析パートは、海外報道・学術研究・公開データを基に編集部が独自に再構成したものです。

※The analytical sections in this article are independently compiled by the Editorial Desk based on international reporting, academic research, and publicly available data.