第一弾:海外が見る「日本はどこへ向かうのか」

—— 高市政権で“懸念”が「進路」へと変わったという見立て

概観:懸念が“確信”に変わりつつある日本

高市政権の誕生で、日本の政治は一見「新しい局面」に入ったように見えます。

しかし、海外の主要メディアやシンクタンクが描く中長期の日本像は、実はほとんど変わっていません。

変わったのは「方向性」ではなく、トーンです。

これまでは「こうなりかねない日本」。

高市政権以後は「もうこの方向で固まりつつある日本」。

Pew Research(2024)では、日本の民主主義の働きに満足していない人が過半数に達しました。

自民党一強、政治資金スキャンダル、長期停滞――。

そうした「慢性的な疲労」の上に、強硬なメッセージを掲げる高市政権が乗ってきた。海外はまずこの構図から日本を見ています。

以下では、海外の分析をもとに、日本の中長期シナリオを

- 民主主義

- 対中・対台・日米同盟

- 経済・財政

- 社会・価値観

の4つの軸で整理していきます。

第1章:民主主義の現在地――「形はリベラル、実態はイリベラル化」

■ イリベラル民主主義とは何か

海外の政治学者が日本を語るとき、必ず出てくるのが

illiberal democracy(イリベラル民主主義=非自由主義的民主主義)という概念です。

難しい話ではなく、本質はシンプルです。

選挙制度は残るが、

メディアの自由・司法の独立・言論の自由・市民の権利といった

“自由の部分”が弱っていく民主主義。

メディアが政権寄りに傾き、権力を監視する機能が後退し、ナショナリズムが支持率の燃料になる――。

こうした「中身が痩せていく民主主義」の典型例として、海外ではハンガリーやポーランドがよく引き合いに出されます。

そして今、日本もまた

「ハンガリー・ポーランド型の非自由主義的民主主義に近づきつつある国」

として語られ始めています。

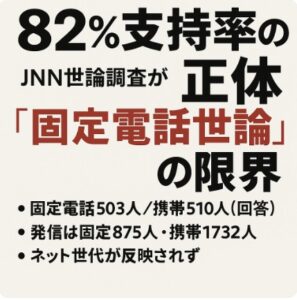

■ 1-1 民主主義そのものへの「不満」がすでに過半数

Pew Research(2024)によれば、

「日本の民主主義の働きに満足していない」人が過半数を超えています。

海外はこの数字を、次のような背景とセットで読み取っています。

- 自民党一強が続くことへの長期的な不信

- 「選挙をしても大勢は変わらない」という諦め

- 高齢化と停滞がもたらす社会全体の閉塞感

手続きとしての民主主義は保たれているものの、

その正当性への信頼は大きく削れている――。

高市政権は、こうした「疲れた民主主義」の土台の上に成立している、と見られています。

■ 1-2 メディアと情報空間の弱さが「民主主義の脆さ」を深めている

Japan Times(2025年10月)は、

人口減少・経済停滞・安全保障不安・メディア報道の歪曲

をまとめて「民主主義を揺るがす複合リスク」として指摘しました。

海外から見ると、日本はすでに

「情報空間そのものが歪みやすい国」として映っています。

2025年に発表された早稲田大学の研究は、日本の有権者が

ロシア・中国など権威主義国家が発信するイリベラルな物語(陰謀論や反自由主義的メッセージ)に

影響されやすい傾向があることを示しました。

しかもそれは、一部の極端な層ではなく、

社会全体に広く見られる傾向だという点が、海外研究者に強い衝撃を与えています。

こうした構造が、海外の政治学者たちに

「日本はハンガリー・ポーランド型の非自由主義的民主主義に近づきつつある」

と言わせる理由になっています。

■ 1-3 ここに「高市早苗」という存在が乗ると、評価が一段変わる

国際報道での高市評はほぼ統一されています。

- hardline conservative(強硬保守)

- ultraconservative / nationalist(超保守・ナショナリスト)

- hawkish politician(タカ派政治家)

とくに海外が懸念するのは、次のような点です。

- 「偏向報道のテレビ局は停波もあり得る」と受け取られた過去の発言

- 日本会議などナショナリスト団体への近さ

- 歴史修正主義的と受け取られる言動

- メディアとの距離が近く、「監視する側/される側」の境界が曖昧になるリスク

- 排外的・感情的なレトリックが支持拡大の“燃料”になりやすい政治構造

もともと日本には、

メディア自粛・政治不信・情報空間の歪み

という「イリベラル化しやすい土壌」がありました。

そこに、イリベラル色の強いリーダーが乗ってきた――。

その結果、海外では

「日本=イリベラル民主主義(非自由主義的民主主義)の予備軍」

というレッテルに、以前よりはるかに説得力がついたと受け止められています。

■ 1-4 「偶然の危機」ではなく、「構造的な進路」

海外の重要なポイントは、

「高市政権だからイリベラル化した」のではないという認識です。

もともと日本は、

- 民主主義への不満が強く

- メディアと情報空間が歪みやすく

- 権威主義的ナラティブにも脆弱

という「弱点」を抱えていました。

そこに、高市早苗という方向性をはっきりさせるリーダーが乗ったことで、

海外からは

日本は「イリベラル化のリスクがある国」から、

「イリベラル化という進路に乗り始めた国」に変わりつつある。

と見えている、というわけです。

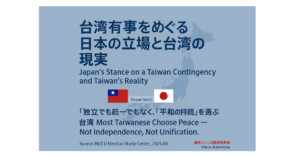

第2章:対中・対台・日米同盟――「前線国家」としての日本が強まる

■ 2-1 台湾発言は「国内政治 × 国際緊張」の悪循環として報じられた

TIME誌「China Is Overreacting to the Japanese Prime Minister’s Taiwan Remarks」は、

高市政権を単なる“タカ派”としてではなく、

「国内政治のために対中強硬を使うリーダー」

として描いています。

高市首相の台湾発言に対し、中国は:

- 日本産水産物の輸入停止

- 日本旅行の自粛呼びかけ

- 対日ナショナリズムの喚起

など、政治・経済・世論を絡めた圧力で応じました。

TIMEの解釈はこうです。

日本は「国内支持を得るための対中強硬発言」を行い、

中国は「国内の不満をそらすための日本叩き」を行う。

その相互作用が、緊張を固定化していく。

これは、ハンガリーやポーランドでも見られた

「国内政治のための外敵設定」と同じパターンだと指摘されています。

■ 2-2 中国は“情報戦×経済戦×世論戦”で日本を揺さぶる構え

中国国防省が

「一線を越えれば痛みを伴う代償を払うことになる」

と日本を名指しで警告したのは象徴的です。

これは単なる軍事的恫喝ではありません。

- 日本企業への“見えにくい圧力”

- SNSや国営メディアを通じた世論戦

- 輸出入や観光を利用した段階的な経済カード

- 台湾海峡や東シナ海での局地的なエスカレーション

こうした複合領域で、日本を消耗させる戦略に中国が移行しつつある――。

海外の安全保障専門家は、そのように見ています。

■ 2-3 日米同盟は「強化」ではなく「依存の固定化」として描かれている

Reutersは高市日本を、

「トランプ2.0時代におけるアジアで最も忠実な同盟国」

と表現しました。

一見すると誉め言葉のようですが、文脈はむしろ批判的です。

海外の懸念はこうです。

- 日本は台湾危機の“前線国家”として使われる

- 日本の判断よりも米国の戦略が優先されがち

- その一方で、日本国内の議論は十分に成熟していない

- 実際の地理的・経済的・軍事的リスクは日本が負う

英Times紙が報じた「トランプが高市に“中国を挑発するな”と警告した」というニュースも、

日本が「主体的なプレーヤー」ではなく、「調整が必要な従属的パートナー」として扱われていることを示しています。

海外から見れば、

日本は“守られる側”から“前線に立つ側”に傾きつつある。

そして、民主主義が疲弊した状態でそれが進むことを、彼らは危険視しています。

第3章:経済・財政――「成長しないまま国家規模だけ膨らむ」危険な方向

■ 3-1 高市経済は「アベノミクス2.5」+「国家プロジェクト膨張」

海外の経済記事(Reuters・FTなど)は、高市政権の経済政策を

おおむね次のように整理しています。

- 積極財政(反緊縮)路線の継続・強化

- 防衛・半導体・AIなどへの大規模な国家支出

- 規制改革や構造改革より、「お金で解決する」方向

- 新規国債発行への依存強化

財政制度等審議会がリフレ政策に歩み寄り、

財政規律を緩める方向に舵を切ったことも、

海外では「懸念材料」として受け止められています。

結局のところ、

「大きな政府と大きな赤字」だけが確実に前へ進む――。

それが、高市経済に対する海外の基本イメージです。

■ 3-2 構造問題は未解決のまま放置されている

海外機関は長年、日本の中長期リスクをこう説明してきました。

- 急速な労働人口減少

- 生産性の伸び悩み

- 移民政策の制約

- 女性活躍・ジェンダー平等の遅れ

- 世界最大級の政府債務残高

- デジタル化・産業構造転換の遅れ

高市政権は、これら構造問題を根本的に変えてはいません。

むしろ、

「ナショナル・プロジェクト中心 → 構造改革が後回し」

という傾向が強まっていると見られています。

海外投資家の一部は、すでにこう語り始めています。

日本は、問題を解決せずに“国家プロジェクト”でごまかす国になりつつある。

■ 3-3 財政が膨らむほど「成長ストーリー」は薄くなる

海外経済紙では、次の懸念が繰り返し指摘されています。

- 新規国債発行が常態化し、マーケットの不信がじわじわ蓄積する

- 防衛費・産業補助金が、必ずしも成長に結びつくとは限らない

- 財政拡大の主要なドライバーが「政治的な人気取り」になっている

- 利上げ局面での金利負担が、中長期的に財政を圧迫する

要するに、

支出は増えるのに、成長の根拠が見えない。

これは「長期停滞の固定化」につながる――というのが、海外の見立てです。

第4章:社会・価値観――経済は開くのに、価値観は閉じるという“ねじれ”

■ 4-1 高市政権は「文化的には超保守」という国際的共通認識

海外メディアは、高市首相の価値観をおおむね次のように描いています。

- 同性婚への一貫した反対

- 選択的夫婦別姓への反対

- 移民・外国人受け入れに対して慎重、むしろ厳格化

- ジェンダー平等・多様性に対する後ろ向きな姿勢

- 歴史修正主義的と受け取られる発言

Mainichi(英語版)は、

「外国人・移民へのスタンスがさらに厳しくなれば、日本社会内部の摩擦を増やす可能性がある」

と報じました。

つまり海外からの理解は一貫しています。

「高市政権の価値観は、経済のグローバル化と逆方向に向かっている」ということです。

■ 4-2 「価値観の閉じた国」は人的資本を失いやすい

国際的には、

価値観が閉じた国ほど、優秀な人材を国内に引き留められない

という認識が広く共有されています。

日本でもすでに、

- 若い世代の海外志向・海外移住の増加

- 女性のキャリア形成の難しさ

- 外国人高度人材の確保難

- 「日本市場の将来性」に懐疑的な海外投資家・外資企業の声

といった現象が目立ち始めています。

海外から見ると、日本は今、

経済はグローバルに開いているのに、価値観は内向きに固まっていく国。

として映っています。

そしてそのねじれが解消されない限り、

「成長の余地そのものが削られていく」という見方が強まっています。

第5章:海外が描く日本の未来シナリオ――「三つの道」

海外の報道や学術論文を整理すると、

高市政権を含めた「日本の行方」は、おおむね次の3つのシナリオに分類できます。

■ シナリオA:「管理されたイリベラル民主主義」として生き延びる

(最も現実的)

- 選挙は続くが、自由・権利・監視機能は痩せていく

- メディアは政権寄りのフレーミングに傾きやすい

- 対中強硬・日米依存は続くが、自律的な外交は弱まる

- 経済は低成長+補助金・バラマキによる延命

- 国民の政治参加は減り、「無関心」が常態化する

いわば、ハンガリー・ポーランドの「アジア版モデル」としての日本です。

■ シナリオB:地政学では重要だが、経済・価値観では周縁化される

- 安全保障では米中対立の「前線国家」として使われ続ける

- しかし、技術・人材・価値観の面では世界の主流から外れていく

- 経済は緩やかな衰退、社会は縮んでいくが、大きな改革は起きない

- 国際社会でのプレゼンスは「偏った形」でだけ維持される

海外の悲観派は、このシナリオを「現在の日本が最も近づいている未来」として描いています。

■ シナリオC:ローカル・市民レベルの民主主義が再生する

(小さな希望)

一方で、よりポジティブな兆しも観察されています。

- 自治体による市民会議・討議型民主主義(ミニ・パブリック)の試み

- 住民投票・ワークショップなど、政策形成への市民参加の拡大

- 草の根レベルでの合意形成や「話し合う政治」の模索

海外の一部研究者は、日本を

国家レベルの民主主義は劣化しているが、

ローカルレベルではむしろ民主主義が再生しつつある国。

として見ています。

ここに、わずかながら「別の未来」の可能性が残されている、という評価です。

結論:高市政権は、日本の「弱点」を固定化する政権として見られている

海外の認識をもっとも正確に一文でまとめるなら、こうなるでしょう。

高市政権は、日本を“急に右に曲げた政権”ではない。

もともと弱っていた民主主義・経済・社会の構造を、

そのまま固定化してしまう政権である。

つまり、海外の視点では:

- 高市政権は「変化」ではなく「固定化」

- 右傾化というより、「非自由主義的民主主義への進路が確定しつつある」

- これまでバラバラに見えていた日本の弱点が、高市政権で一つの輪郭を持ち始めた

総評

海外は、日本の“強さ”よりも“弱点”をよく見ている。

強硬なスローガンも、タカ派の演出も、

構造の脆さを覆い隠すものにはならない。

むしろ高市政権は、

日本が抱えてきた問題の“答え合わせ”をしてしまった。

つまり、悪い予測ほど当たってしまった国——という評価だ。

今の日本は、右傾化というより“薄氷の上で強がる国”。

海外には、そう見えている。

Part 1: Where Is Japan Heading?

How Overseas Observers Interpret the Takaichi Administration as a Shift from “Concern” to “Trajectory”

Prologue: Japan’s Warning Signs Are Turning Into a Trajectory

At first glance, the inauguration of Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi looks like a major turning point in Japanese politics.

But when you read what major international media and think tanks are saying, a different picture emerges:

their medium- to long-term view of Japan has hardly changed.

What has changed is not the direction, but the tone.

Before Takaichi: “Japan might be heading this way.”

After Takaichi: “Japan is now effectively on this path.”

A 2024 Pew Research survey shows that a majority of Japanese are dissatisfied with how democracy works in their country.

Long-ruling LDP governments, money scandals, and economic stagnation have produced a kind of chronic fatigue.

On top of that, a hardline leader with strong rhetoric has now appeared.

From abroad, this combination—

a tired democracy plus a hardline prime minister—

is the starting point for thinking about where Japan is heading.

In what follows, we summarize the main overseas narratives about Japan’s future along four axes:

- Democracy

- China, Taiwan and the U.S.–Japan alliance

- Economy and public finances

- Society and values

Chapter 1: Democracy Today — Liberal in Form, Illiberal in Substance

■ What “illiberal democracy” means (setting the terms)

When foreign political scientists discuss Japan, they almost always use the term

“illiberal democracy.”

In Japanese, this is often rendered as

「イリベラル民主主義(非自由主義的民主主義)」.

The idea itself is simple:

Elections remain, but the core “freedoms” of democracy—

free media, judicial independence, freedom of speech, and citizens’ rights—

gradually weaken.

Media grow closer to the ruling party, checks and balances erode, and nationalism becomes fuel for approval ratings.

This pattern of a “democracy with shrinking substance” is most often associated with Hungary and Poland.

Increasingly, Japan is being discussed as a country that is

moving closer to the Hungarian/Polish model of illiberal democracy.

■ 1-1 Growing dissatisfaction with democracy

According to Pew Research (2024), a

majority of Japanese say they are dissatisfied with how democracy works

in their country.

Foreign observers read this against several structural factors:

- long-term distrust toward the dominant LDP,

- a sense that “elections don’t really change anything,”

- deep social stagnation driven by aging and low growth.

In other words, the procedures of democracy remain in place,

but public confidence in its substance has been badly eroded.

The Takaichi administration stands on top of this already weakened foundation.

■ 1-2 A weak media and distorted information space deepen democratic fragility

A 2025 Japan Times commentary highlighted demographic decline, economic stagnation, security pressures,

and media distortions as a set of interlocking risks to Japan’s democratic stability.

From abroad, Japan increasingly looks like

a country whose information space is structurally prone to distortion.

A 2025 study by Waseda University found that Japanese citizens are

surprisingly vulnerable to authoritarian narratives

propagated by states like Russia and China—conspiracy-like stories and anti-liberal messaging.

Crucially, this vulnerability is not limited to a small extremist fringe;

it appears across society as a whole. This has deeply alarmed many researchers.

These findings underpin a growing view among political scientists that

Japan is moving closer to the Hungarian/Polish pattern of illiberal democracy.

■ 1-3 How Sanae Takaichi changes the picture

International coverage of Takaichi is remarkably consistent. She is typically described as:

- a hardline conservative,

- an ultraconservative or nationalist,

- a hawkish politician.

Specific concerns repeatedly mentioned abroad include:

- her past remark suggesting that broadcasters with “biased” coverage could face suspension,

- her closeness to nationalist and revisionist groups,

- a media environment at risk of becoming too cozy with political power,

- a political dynamic in which emotional, exclusionary rhetoric boosts approval ratings.

Japan already had

a tendency toward media self-censorship, political distrust, and a distorted information space.

On top of that, a leader with a strong illiberal affinity has now taken office.

As a result, many observers now feel that the label

“Japan as a pre-illiberal democracy”

has gained much more credibility than before.

■ 1-4 Not an “accidental crisis,” but a structural trajectory

A key point in overseas analysis is this:

Japan did not suddenly become illiberal because of Takaichi.

Rather, Japan already had:

- widespread dissatisfaction with democracy,

- a media and information space prone to distortion,

- and a public vulnerable to authoritarian narratives.

Takaichi’s rise, in this view, simply gives

a clear direction and face to trends that were already there.

This is why many foreign analysts now describe Japan as:

a country that has moved from “at risk of illiberalism”

to being “effectively on an illiberal trajectory.”

Chapter 2: China, Taiwan and the U.S.–Japan Alliance — Japan as a Frontline State

■ 2-1 Taiwan remarks as a cycle of “domestic politics × regional tension”

In its piece “China Is Overreacting to the Japanese Prime Minister’s Taiwan Remarks,”

TIME portrays Takaichi not just as a hawk, but as

a leader who uses toughness on China for domestic political gain.

After Takaichi’s remarks on Taiwan, Beijing:

- restricted or halted imports of Japanese seafood,

- discouraged travel to Japan,

- and ramped up anti-Japan nationalism at home.

TIME’s core argument is that:

Japan uses anti-China toughness to win support at home, while

China uses Japan-bashing to deflect discontent at home.

This mutual use of each other locks the region into chronic tension.

Analysts note that this resembles what happened in Hungary and Poland—

“external enemies” being used to stabilize domestic politics.

■ 2-2 China’s mix of information, economic, and opinion warfare

When China’s Defense Ministry warned that Japan would “pay a painful price” if it crossed certain lines on Taiwan,

foreign experts did not see this as only military signaling.

They instead point to a broader toolbox:

- subtle pressure on Japanese firms and investments,

- information operations via social media and state media,

- calibrated use of trade and tourism as economic levers,

- and limited escalation in the Taiwan Strait and East China Sea.

The Global Taiwan Institute, among others, frames this as

a strategy to weaken U.S.–Japan–Taiwan coordination by raising the cost for Japan.

■ 2-3 The U.S.–Japan alliance: strengthened, or structurally dependent?

Reuters has described Japan under Takaichi as

“the most loyal ally in Asia under a Trump 2.0 scenario.”

This is hardly a straightforward compliment.

Foreign concerns include:

- Japan being treated as the frontline platform in U.S. strategy toward China,

- an expanded Japanese role in any Taiwan contingency,

- insufficiently mature domestic debate in Japan on these high-stakes issues,

- and the reality that Japan—not the U.S.—bears the geographic and economic risks.

A British report that Trump privately told Takaichi “don’t provoke China” reinforces the impression that

Japan is seen more as a subordinate partner to be managed than as a fully autonomous actor.

From abroad, then, it increasingly looks like:

Japan is drifting from “protected ally” toward “frontline state.”

And that shift is happening at a time when Japan’s own democracy is weakening.

Chapter 3: Economy and Public Finances — “A State That Grows Bigger Without Growing Faster”

■ 3-1 Takaichi’s economics as “Abenomics 2.5” plus swelling national projects

International economic coverage (Reuters, FT and others) tends to summarize Takaichi’s economic policy as:

- continued and intensified expansionary fiscal policy,

- large-scale state spending on defense, semiconductors and AI,

- a preference for “money solutions” over structural reforms,

- and a stronger reliance on government bonds.

Japan’s Fiscal System Council has effectively shifted toward a more reflationist stance,

loosening its emphasis on fiscal discipline.

For foreign investors, this is another worrying sign.

In short, the emerging image is:

“bigger government and bigger deficits” are moving ahead—but growth is not.

■ 3-2 Structural problems remain largely untouched

For years, international institutions have highlighted Japan’s long-term risks:

- rapidly shrinking working-age population,

- stagnant productivity,

- political resistance to large-scale immigration,

- slow progress on gender equality and diversity,

- one of the highest public debt ratios in the world,

- and sluggish digital and industrial transformation.

Takaichi’s policies have not fundamentally changed any of these.

If anything, there is a stronger tilt toward

national projects first, structural reform later (if ever).

As one skeptical investor put it:

Japan is becoming a country that papers over problems with national projects instead of solving them.

■ 3-3 The more debt expands, the thinner the growth story becomes

Foreign economic commentary repeatedly stresses several points:

- new government bond issuance is becoming normalized, slowly eroding market confidence,

- defense and industrial subsidies may not translate into sustainable growth,

- fiscal expansion is increasingly driven by political popularity,

- and rising interest rates will eventually raise the cost of debt service.

Put simply:

spending is rising, but the growth story is not getting clearer.

Many analysts see this as a recipe for “long-term stagnation made semi-permanent.”

Chapter 4: Society and Values — An Open Economy with a Closing Mindset

■ 4-1 Culturally ultra-conservative: the consensus foreign view of Takaichi

In the social and cultural realm, foreign media tend to summarize Takaichi’s positions as:

- firm opposition to same-sex marriage,

- opposition to separate family names for married couples,

- a cautious or restrictive stance toward immigration,

- reluctance on gender equality and diversity,

- and a record of statements seen as historically revisionist.

The English edition of Mainichi has warned that a tougher stance on foreigners and immigrants

could increase social friction within Japan.

In short, the foreign consensus is that

“Takaichi’s social values run counter to the direction of Japan’s globalized economy.”

■ 4-2 Countries with closed values tend to lose human capital

International experience suggests that

countries with closed social values struggle to retain or attract top talent.

In Japan, several trends are already visible:

- more young people expressing interest in living or working abroad,

- systemic obstacles to women’s career advancement,

- difficulties in attracting highly skilled foreign workers,

- and foreign investors questioning Japan’s future dynamism.

From abroad, Japan increasingly looks like:

an economy that is open to the world,

coupled with a society whose values are turning inward.

Unless this contradiction is addressed,

many fear that Japan’s growth potential itself will continue to shrink.

Chapter 5: Three Scenarios for Japan’s Future

Bringing together overseas reporting and scholarly work,

Japan’s trajectory under and beyond the Takaichi administration can be grouped into three broad scenarios.

■ Scenario A: A Managed Illiberal Democracy (the most likely)

- elections continue, but freedoms and checks and balances erode,

- media coverage becomes increasingly government-friendly,

- toughness toward China and reliance on the U.S. remain central,

- the economy is kept alive through subsidies and handouts rather than genuine reform,

- citizen participation declines, and political apathy becomes the norm.

In effect, Japan becomes an

“Asian version” of the Hungarian/Polish model.

■ Scenario B: Geopolitically central, economically and normatively peripheral

- Japan remains a key frontline state in U.S.–China rivalry,

- but falls behind in technology, talent, and global norms,

- economic decline is slow but persistent, and reforms remain partial,

- Japan’s international profile becomes narrow and security-centric.

Pessimistic analysts see this as the scenario Japan is already drifting toward.

■ Scenario C: Democratic renewal from below (a small but real source of hope)

There is, however, a more hopeful story emerging at the local level.

- citizens’ assemblies and deliberative mini-publics organized by municipalities,

- local referendums and workshops on energy, climate, and urban planning,

- experiments in “talking politics” beyond party and factional boundaries.

Some foreign researchers now describe Japan as:

a country where democracy is deteriorating at the national level,

but being quietly reinvented at the local level.

In this sense, there is still a narrow opening for

a different future—if these bottom-up experiments can grow.

Conclusion: A Government That Locks In Japan’s Weaknesses

The most accurate one-sentence summary of the overseas view might be this:

The Takaichi administration has not suddenly “turned Japan to the right.”

Rather, it is consolidating structural weaknesses that were already there—

in democracy, the economy, and society.

From this perspective:

- Takaichi represents not so much “change” as “lock-in,”

- Japan is moving from “at risk of illiberalism” to “on an illiberal course,”

- and long-standing weaknesses are finally acquiring a clear shape.

Final Assessment

Foreign observers see Japan less for its strengths and more for its underlying vulnerabilities.

No slogan of toughness, no display of hawkishness can conceal the structural fragility beneath.

In fact, the Takaichi administration has merely confirmed the problems Japan has long avoided facing.

To many abroad, Japan has become a country where the worst predictions are turning out to be true.

Today’s Japan is not so much “moving to the right” as it is trying to look strong while standing on thin ice.

That is how the country now appears from the outside.

参考文献(References)

- Pew Research Center (2024)

- Japan Times (2025)

- Waseda University Study (2025)

- Reuters — Japan/Asia-Pacific

- TIME Magazine

- The Times (UK) – International Edition

- Reuters — Markets/Asia

- Financial Times – Japan

- Mainichi Shimbun (English Edition)

- Global Taiwan Institute

※本記事の分析パートは、海外報道・学術研究・公開データを基に編集部が独自に再構成したものです。

※The analytical sections in this article are independently compiled by the Editorial Desk based on international reporting, academic research, and publicly available data.

コメント

コメント一覧 (2件)

海外の方から見た興味深い分析だと思います。

コメントありがとうございます。

海外からの視点は、国内ではあまり語られない部分が見えてくるので、

日本の現状を理解する上で重要だと感じています。

今後も続編を公開していきますので、

また読んでいただけたら嬉しいです。