「質問通告が遅い」というデマが示す、日本政治の“逆転構造”

「野党の質問通告が遅い」という政府側の主張は、事実ではなかった。

しかしその言い訳が、SNS上で政治の“常識”として拡散された。

それは日本の政治文化に根づく、説明責任の逆転構造を映し出している。

第一章:午前3時の「勉強会」が象徴したもの

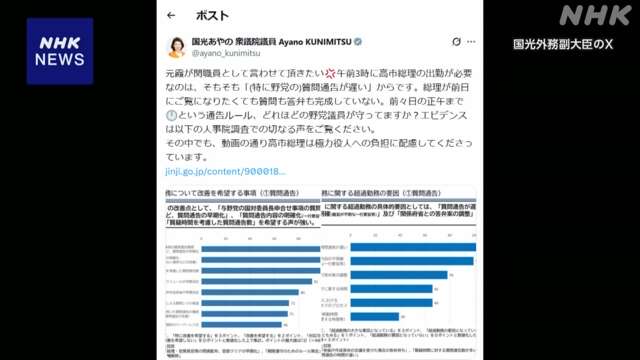

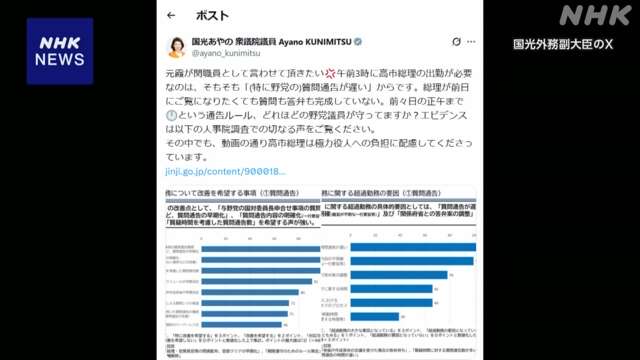

高市首相が午前3時ごろに官邸で答弁打ち合わせを行い、その様子を国光外務副大臣がSNSに投稿しました。

「野党の質問通告が遅いから、総理は深夜まで仕事をしている」という趣旨でしたが、これは事実ではありませんでした。

野党側はルール通り、前々日の正午までに質問を通告していました。

その後、国光氏は投稿を削除し「誤解を招いた」と謝罪。木原官房長官も、事実誤認であったことを認めました。

この時、私はこの事自体に強い違和感を覚え、次のようにXに投稿しました。

この違和感は、「質問通告」をめぐる日本の政治文化が、他の民主主義国の常識とはあまりにかけ離れていることに気づいたからです。

では、各国の民主主義国では、どのように「質問」と「説明責任」が成り立っているのでしょうか。

第二章:資本主義国で「質問通告」を盾にする国はほとんどありません

日本で「野党の質問通告が遅い」といった言い訳が通用するのは、資本主義国の中でも極めて珍しいことです。

立法府による行政監視の根幹は、「準備が整っていなくても、その場で説明できること」にあります。

それは単なる政治スキルではなく、民主主義の筋力そのものです。

イギリスでは、首相が野党の質問を事前に知らされないまま答える「首相質問(Prime Minister’s Questions)」が制度として定着しています。

議員の一言一言に対して首相が即座に反論や答弁を行い、その様子が全国に中継されます。

この緊張感こそが、政治の「透明性」を支えているのです。

カナダやオーストラリアの議会でも、「質問時間(Question Period / Question Time)」では事前通告は形式的なものにすぎず、質問文の全文を伝える必要はありません。

閣僚は即興で答えることを求められ、「準備ができていないから答えられない」という言い訳は通用しません。

むしろ、そうした対応は失格の印と見なされます。

そしてアメリカでは、制度の形こそ違いますが、根底にある考え方は同じです。

大統領が議会で質問を受けることはありませんが、その代わりに強力な「公聴会(Congressional Hearings)」制度があります。

議員は政府高官や企業幹部を呼び出し、事前通告なしで自由に質問することができます。

それが立法府による行政監視――いわば“質問の権力”なのです。

公聴会では、官僚が答弁書を読み上げるようなことはありません。

議員の質問を「想定問答集」で回避することもできません。

議員は核心を突く質問を投げかけ、時に挑発的に切り込みます。

その場でどう答えるかが、職責と信頼を測る尺度になります。

アメリカ議会調査局(CRS)は、「監視の本質は、行政が不意の質問にも説明できることにある」と明記しています。

つまり、準備されていない瞬間こそ、民主主義の真価が試されるということです。

行政の答弁を“安全運転化”する日本の通告文化は、その原理を逆転させてしまっています。

こうした国々では、「質問に備えること」よりも、「問われたときに答えること」に価値が置かれています。

その違いが、政治文化の成熟度を決定づけているのです。

「通告が遅い」という言い訳がまかり通る社会では、政治家は“想定外”を恐れ、市民は“想定内”の答弁に慣らされていきます。

民主主義は、そうして静かに退化していくのです。

出典:

UK Parliament – Prime Minister’s Questions / U.S. Congressional Research Service – Congressional Oversight Manual / Parliament of Canada – Question Period / Parliament of Australia – Question Time

第三章:民主主義の首を締めるとは何か

民主主義は、本来とても“めんどうな”制度です。時間がかかり、異論が出て、行政にとっては不便です。

しかし、その不便さこそが暴走を防ぐ安全装置になっています。

ところが、「効率よく答弁したい」「政権のメンツを守りたい」という理由で、野党の質問を狭めていくと、国会はあっという間に“演出された場所”に変わります。

官僚が台本を作り、政治家がそれを読み、国民がそれを“いつもの国会風景”として受け入れてしまう。

これは静かな窒息です。

日本では「失言を避ける」ことが政治家の能力とされがちですが、本来はそうではありません。

世界の民主主義国では、「どんな質問にも自分の言葉で答えること」こそが信頼の基準になっています。

政治とは台本の朗読ではなく、その場で価値観を問われる仕事だからです。

しかし日本では、官僚が答弁書を作り、政治家がそれを読む光景が日常化しています。

政治家の言葉が「本人の言葉」として響かないのは当然です。

有権者がそれを許してしまう限り、政治は変わりません。

民主主義の首を締めるのは、独裁者だけではない。

それを見て見ぬふりをする市民の沈黙もまた、民主主義を弱らせる。

(民主主義思想に基づく筆者の言葉)

今回の「質問通告が遅い」というデマを庇おうとする人たちは、気づかないうちに自分たちの側の「知る権利」や「権力を問いただす権利」まで手放しています。

政権のために擁護しているつもりでも、実際には民主主義の首を自分で締めているのです。

民主主義とは、都合の悪い質問を避けることではなく、正面から受け止めることです。

たとえ不完全でも、誠実な言葉で答える政治家が評価される社会に戻していかなければなりません。

その一歩は、私たち有権者が「即興の言葉」を信じられるかどうかにかかっています。

Democracy doesn’t die in chaos. It dies in silence.

民主主義は混乱の中で死ぬのではない。沈黙の中で死ぬのだ。

— Inspired by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt, How Democracies Die (2018)

Chapter 1: What the 3 a.m. “Briefing” Really Revealed

At around 3 a.m., Prime Minister Takaichi held a briefing at the Kantei to prepare for Diet questions. Deputy Foreign Minister Ayano Kunimitsu posted about it on X, claiming that “the opposition submitted their questions too late.” However, that statement was factually incorrect. The opposition parties had already submitted their questions by the official deadline—noon, two days earlier.

Kunimitsu later deleted the post, apologized for the misunderstanding, and Chief Cabinet Secretary Kihara also admitted that the claim was based on false information. This episode—what became known as the “3 a.m. study session”—revealed something deeper about Japan’s political culture: a tendency to resent being questioned at all.

Witnessing this, I felt a strong sense of unease and shared the following post on X, questioning why such attitudes are tolerated in a democracy.

What struck me was how the government’s narrative—blaming the “lateness” of question submissions—felt fundamentally at odds with the democratic norms of other nations. So, how do mature democracies actually handle questions and accountability?

Chapter 2: In Mature Democracies, Governments Rarely Hide Behind “Question Notices”

In most capitalist democracies, it is extremely rare for a governing party to excuse itself by blaming the opposition for “late question submissions.” The essence of legislative oversight lies precisely in the ability to respond— even when unprepared. That ability is not just a political skill, but the very muscle of democracy.

In the United Kingdom, the Prime Minister faces unscripted questions every week during Prime Minister’s Questions (PMQs). Questions are not disclosed in full beforehand, and the exchanges are broadcast live across the nation. This ritual of spontaneous accountability is one of the cornerstones of British democracy.

Canada and Australia also hold similar sessions known as Question Period and Question Time. Ministers are expected to answer on the spot; “we weren’t ready” is not an acceptable excuse. In fact, being unable to respond spontaneously is often seen as a sign of political weakness.

In the United States, the same democratic principle is expressed through Congressional Hearings. Lawmakers summon senior officials and corporate executives, questioning them freely—often without prior notice. Bureaucrats do not read pre-approved scripts; the credibility of leaders is tested by how they answer in real time.

The U.S. Congressional Research Service (CRS) defines the essence of oversight as “the ability of the executive branch to explain itself under unanticipated questioning.” In that sense, Japan’s bureaucratic culture of exhaustive preparation represents a reversal of this democratic ideal.

In these democracies, value is placed not on “preparing for questions,” but on “answering when asked.” That distinction defines political maturity. When a society normalizes excuses like “the notice was late,” politicians grow afraid of improvisation— and citizens, in turn, grow accustomed to pre-scripted performances. Democracy doesn’t collapse overnight; it quietly withers away.

Sources:

UK Parliament – Prime Minister’s Questions

Parliament of Canada – Question Period

Parliament of Australia – Question Time

U.S. Congressional Research Service – Congressional Oversight Manual

Chapter 3: What It Means to “Strangle” Democracy

Democracy is, by nature, inconvenient. It takes time, disagreements arise, and the executive cannot always control the tempo. Yet that very inconvenience is what prevents the abuse of power.

When governments begin to narrow questioning in the name of “efficiency” or “saving face,” legislatures quickly turn into stages for pre-scripted performances. Bureaucrats draft the lines, politicians read them, and the public accepts it as the norm. This is not democracy—it is quiet suffocation.

In Japan, avoiding verbal missteps is often mistaken for political competence. But in healthy democracies, the true measure of leadership lies in the ability to respond in one’s own words. Politics is not about reading from a script; it is about being accountable in real time.

However, in today’s Japan, bureaucrats write the answers and politicians merely perform them. When words no longer carry the speaker’s conviction, politics loses its vitality— and citizens, accustomed to that hollowness, cease demanding authenticity.

It is not only dictators who strangle democracy —

the silence of citizens who look away weakens it just as surely.

(A reflection by the author, rooted in democratic thought)

Those who defend the “late question notice” narrative may not realize it, but they are quietly surrendering their own right to question power. They believe they are protecting “their government,” when in truth, they are tightening the rope around democracy itself.

Democracy does not die in chaos. It dies in silence.

— Inspired by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt, How Democracies Die (2018)